Laboratory safety & hygiene equipment

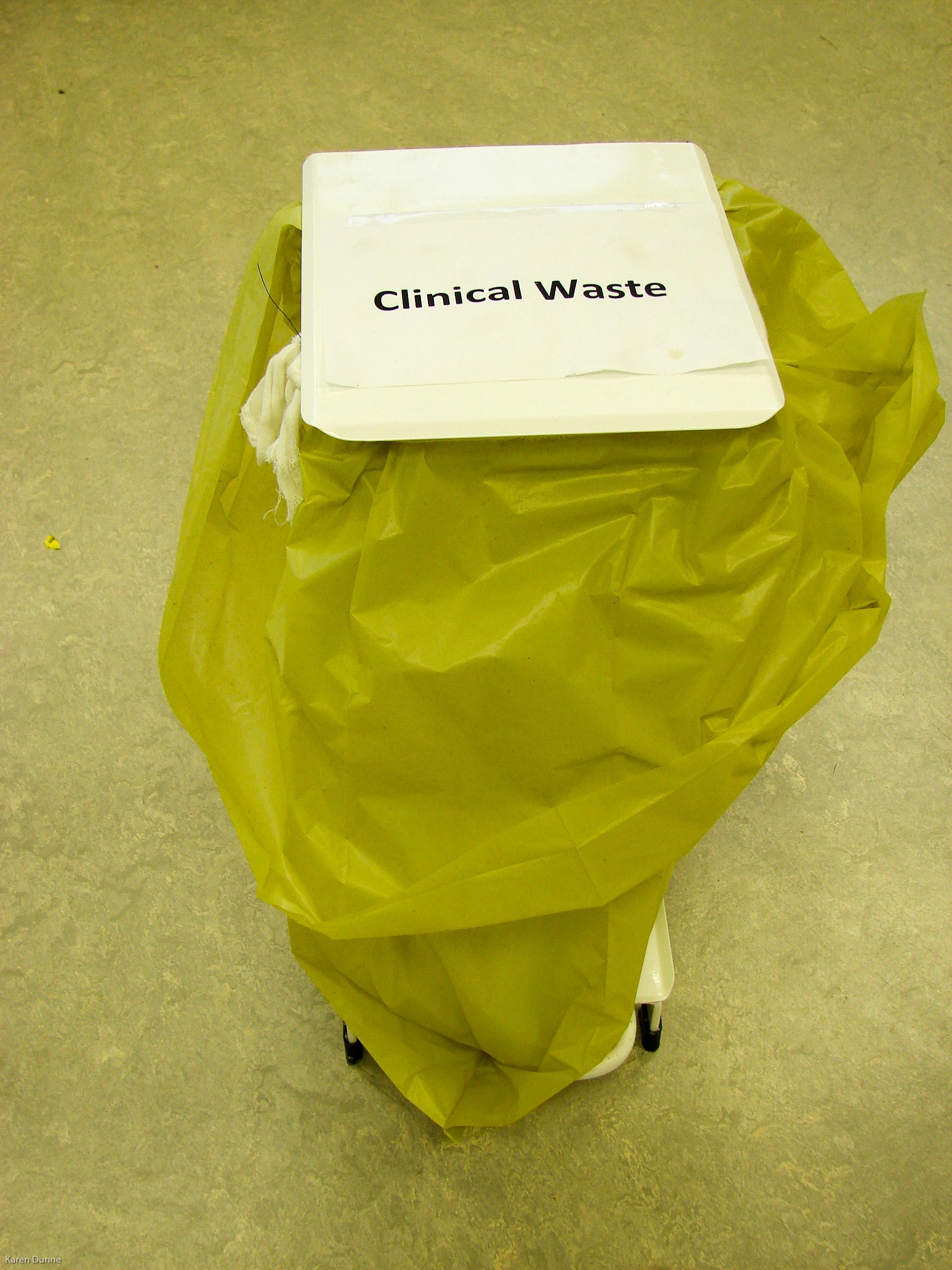

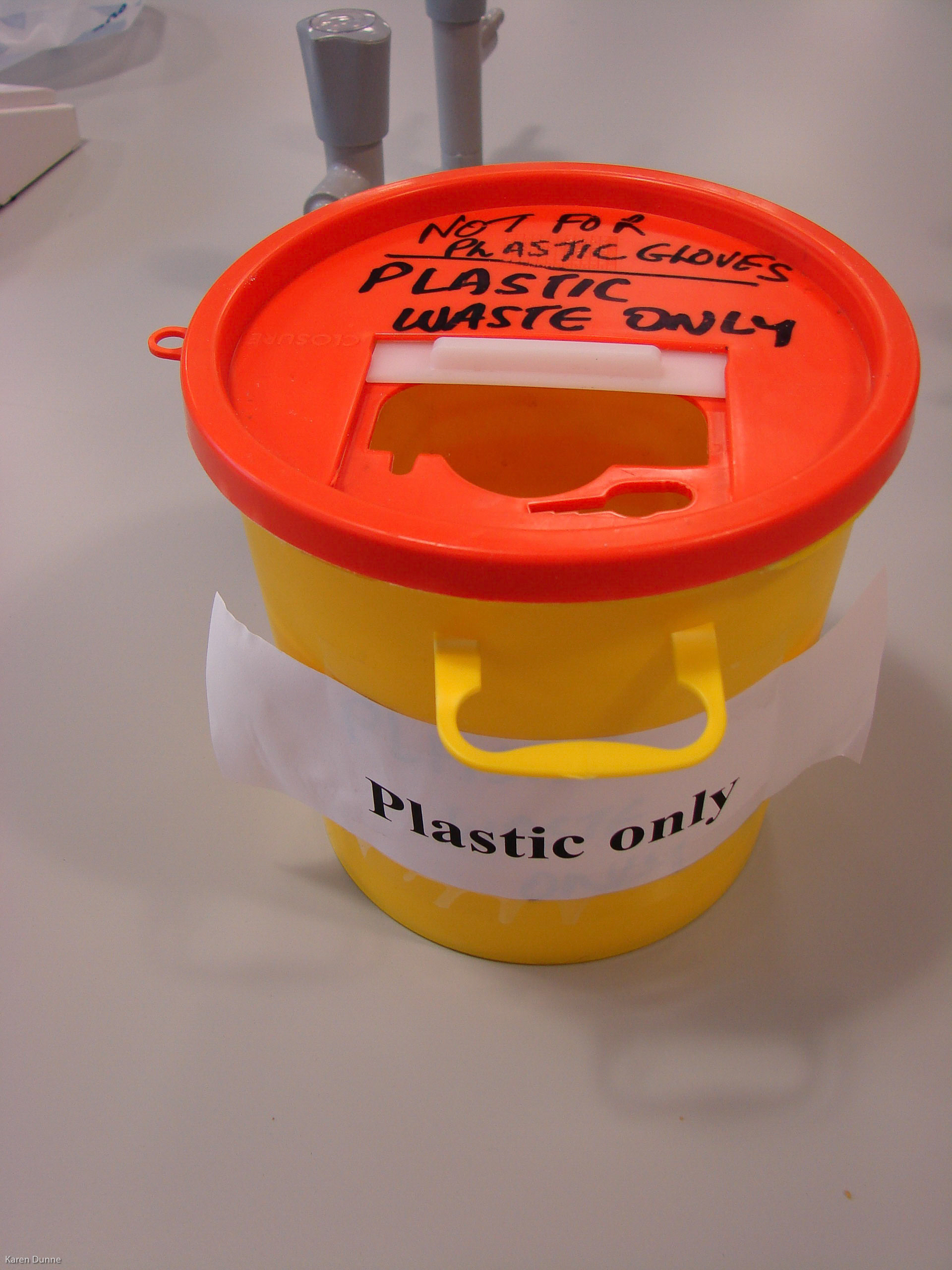

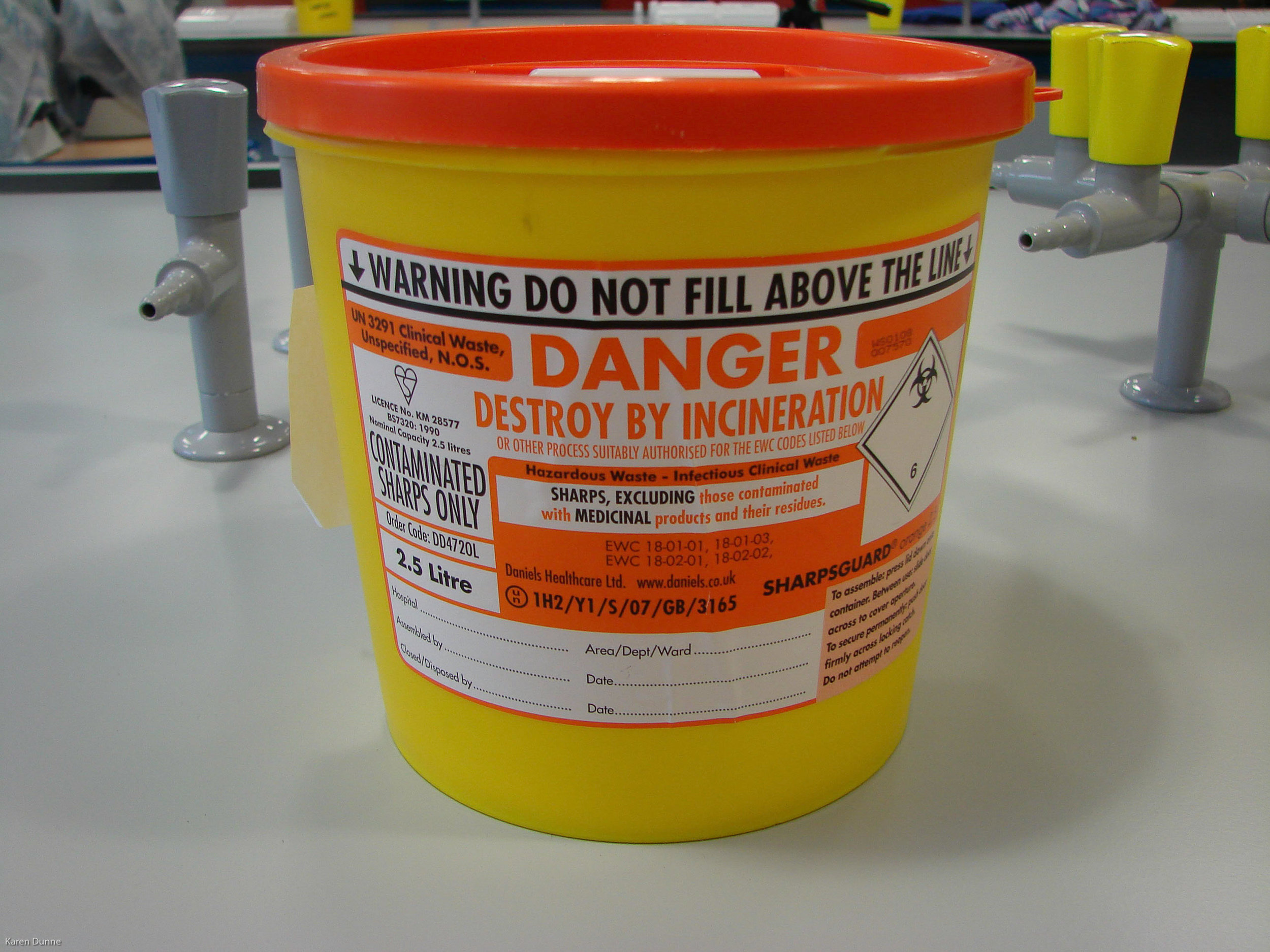

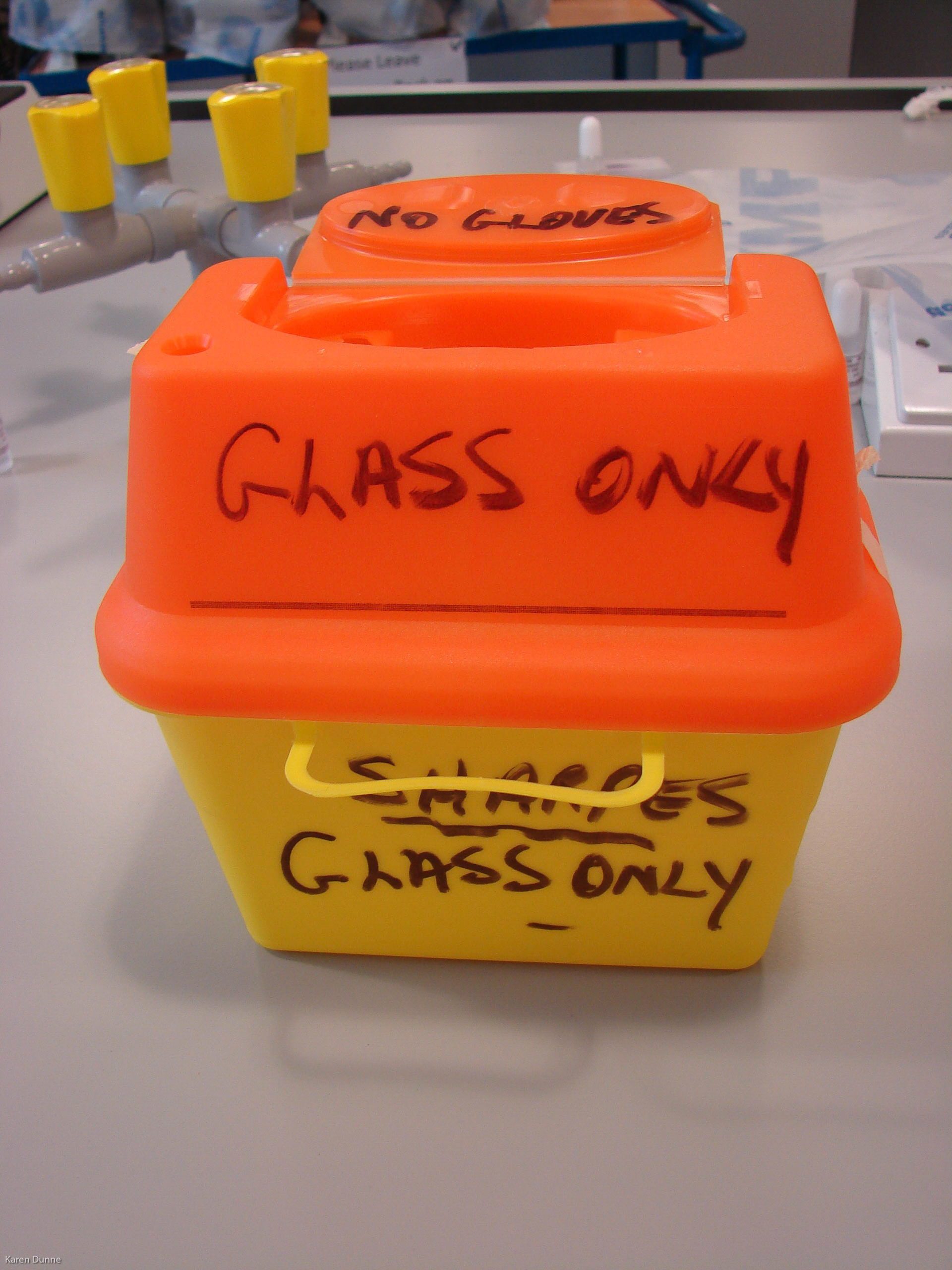

Waste disposal in the laboratory

Classification of biosafety levels

Biosafety level 1

These are agents that do not normally cause disease in humans (although individuals with immune deficiency may be affected).

Examples include soaps, detergents and cleaning agents, animal vaccines and non-zoonotic/specifies-specific infectious diseases e.g. canine parvovirus or feline immunodeficiency virus.

There are no specific safety requirements when handling or disposing of these agents beyond that of normal sanitation and rubbish disposal, such as would be used in a home kitchen e.g. washing hands, work surfaces and equipment.

Biosafety level 2

These have the potential to cause disease in humans if handled incorrectly. Specific precautions should be taken to avoid problems such as oral ingestion, skin puncture or mucous membrane exposure. However these organisms are generally rarely transmitted via aerosols or inhalation. Examples include Toxoplasma gondii and Salmonella spp.

General requirements include:

- Limited access to the area.

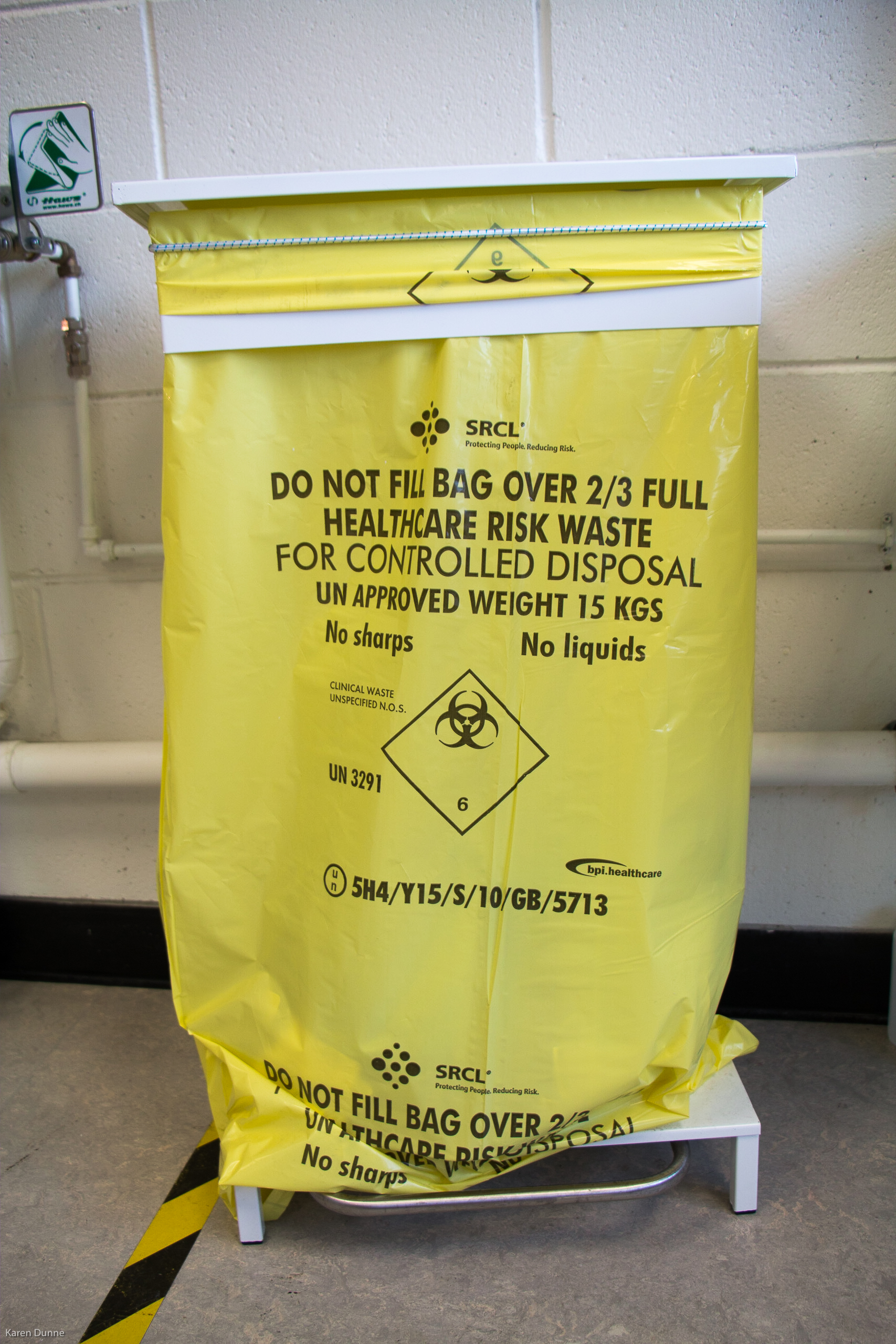

- The use of biohazard warning signs.

- Wearing of gloves, lab coat/gown, face shield.

- Use of Class I/II biosafety cabinets to reduce the risk of splashes and aerosols.

- Careful use of sharps containers e.g. no needles in bags.

- Specific protocols for disposal or cleaning/decontamination of equipment.

- Physical containment devices if necessary.

- Autoclaving to destroy the organisms.

Biosafety level 3

These are substances that can cause serious and potentially fatal disease in humans. There is also a high risk of aerosols e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis or highly pathogenic avian influenza. Primary and secondary barriers are needed to protect people. There are not many veterinary pathogens in this category.

General requirements include:

- Controlled access.

- Decontamination of waste.

- Use of protective clothing/gear by all personnel.

- Decontamination of accommodation & equipment.

- Testing of personnel to check for possible exposure.

- Use of cabinets and containment devices in all cases.

Biosafety level 4

Agents that pose a high risk of life-threatening disease in humans e.g. Ebola or Marbury virus. It is very unlikely that these will be encountered in a veterinary context. Individuals working with these agents require extensive specialist training. Safety precautions include human isolation units, showering in and out and full body suits with a positive air supply.

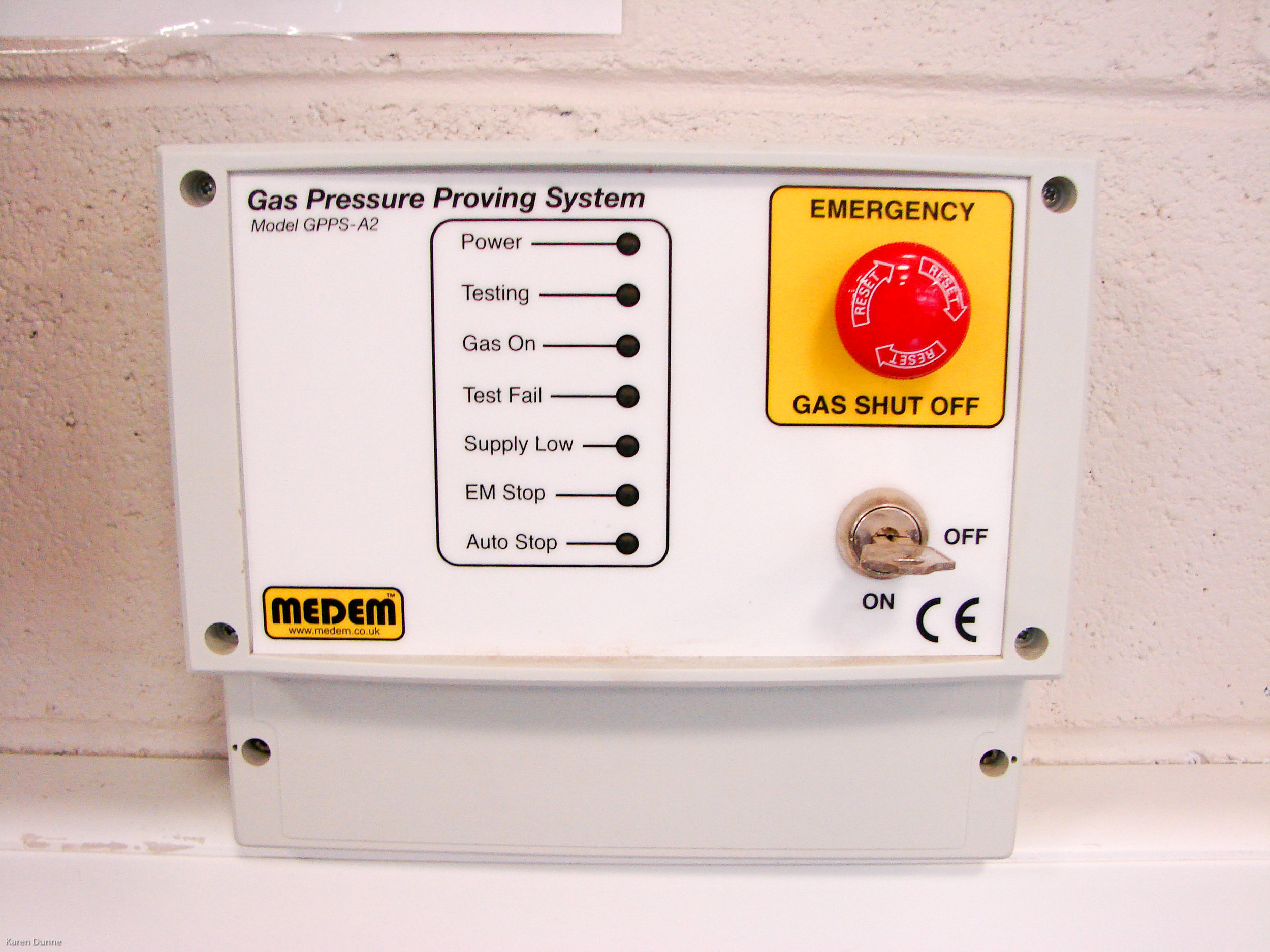

Laboratory essentials

Effective hygiene and biosecurity is required to reduce the risk of contamination of both the patient and the sample being collected. It also decreases the risk of zoonotic disease transmission.

Components of laboratory hygiene:

- Protective clothing

- Hand washing

- Hand sanitisation

- Disposable gloves

- Using sterile equipment

- Aseptic technique

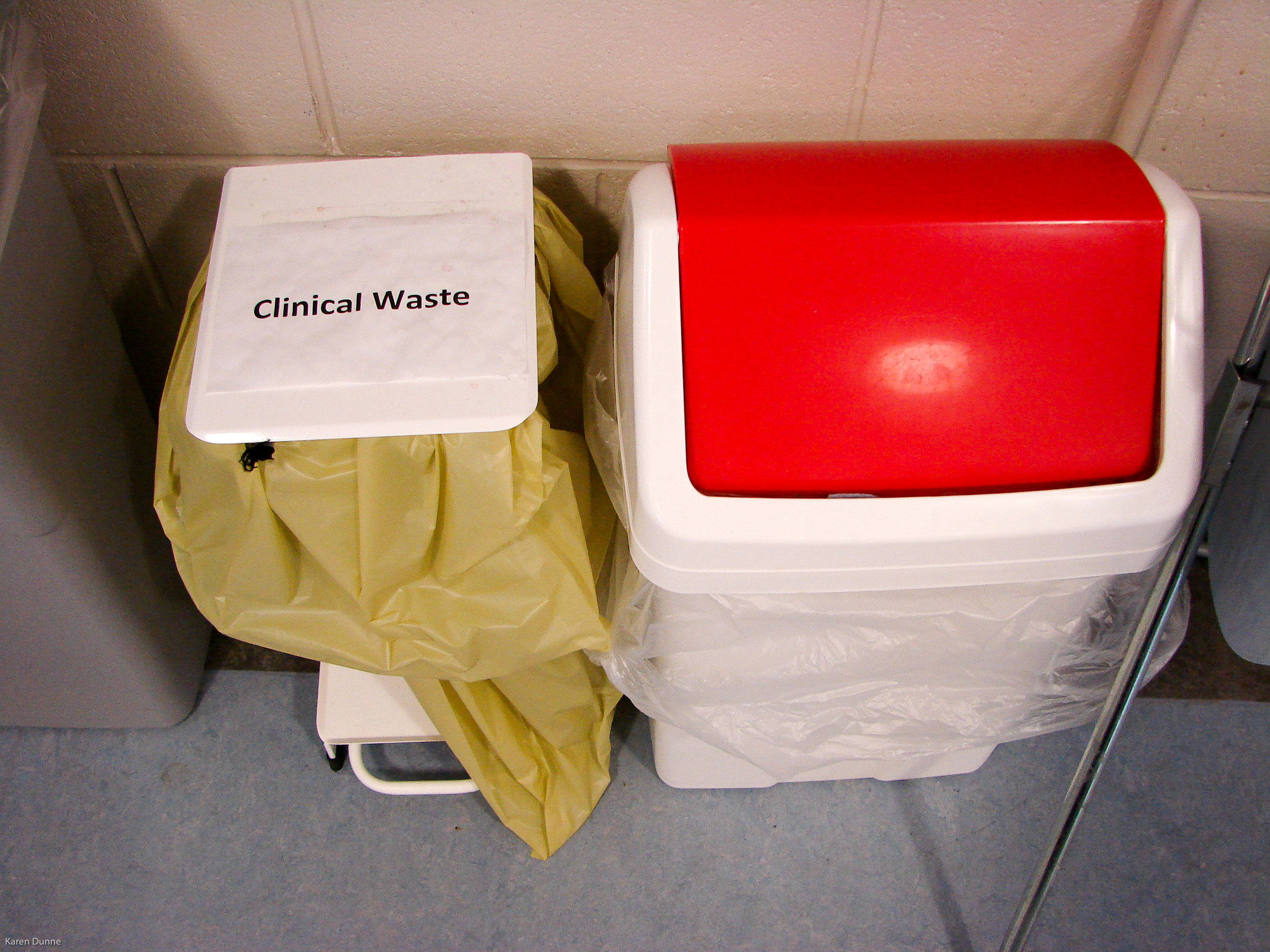

- Waste disposal

- Laboratory conduct

Jewellery should be kept to a minimum and avoid nail varnish. Nails should be kept short and clean. Disposable gloves in a range of sizes should be readily available. Do not place anything in your mouth while in the lab or lick gummed labels etc. A wash basin should be reserved for hand washing and equipped with liquid antibacterial soap and paper towels (see below).

The work surfaces should be cleaned and wiped down with disinfectant daily and after every procedure involving body tissues/fluids and/or potentially harmful reagents. Keep the lab clean and tidy with all items correctly cleaned and stored away after use.

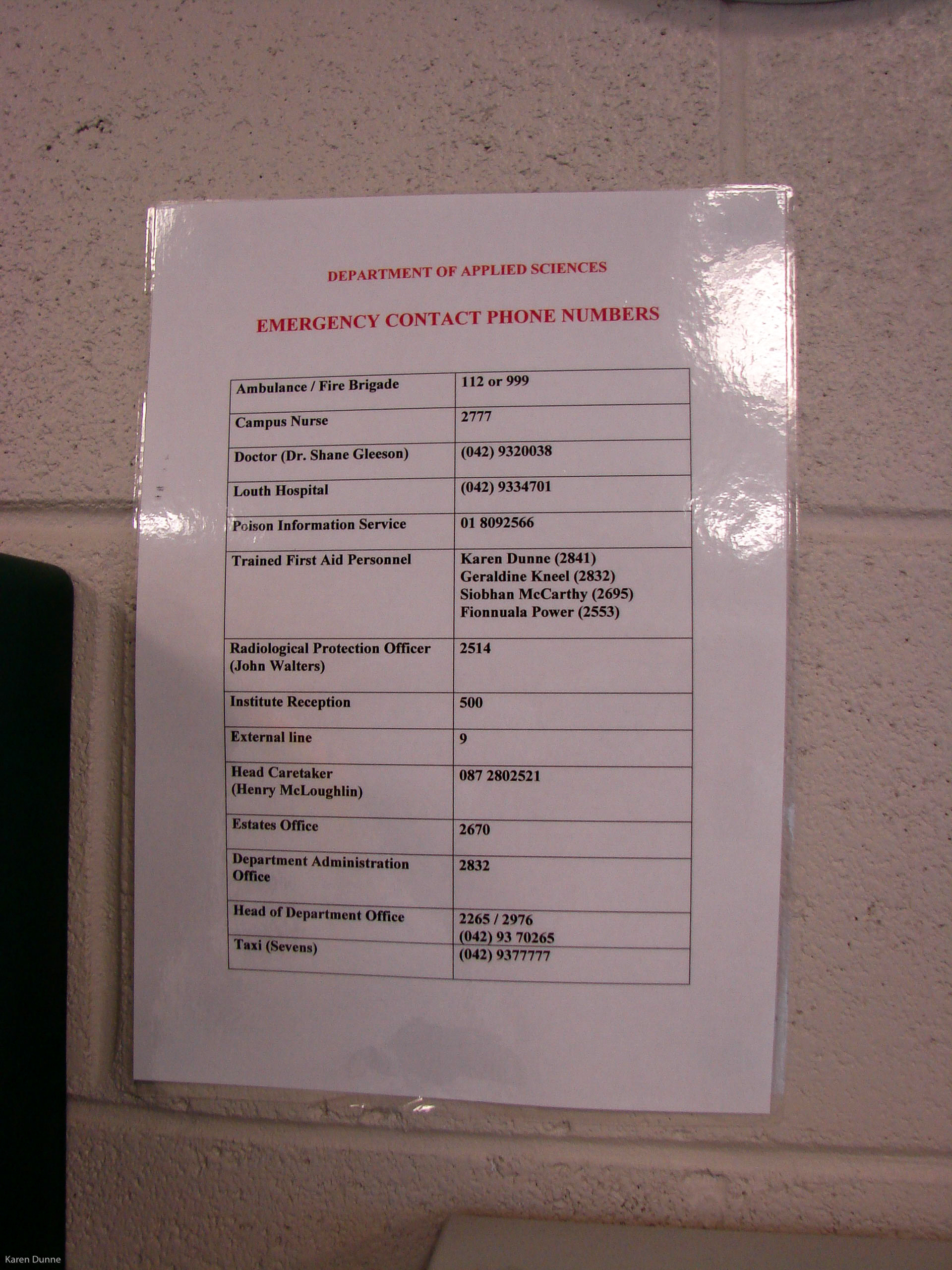

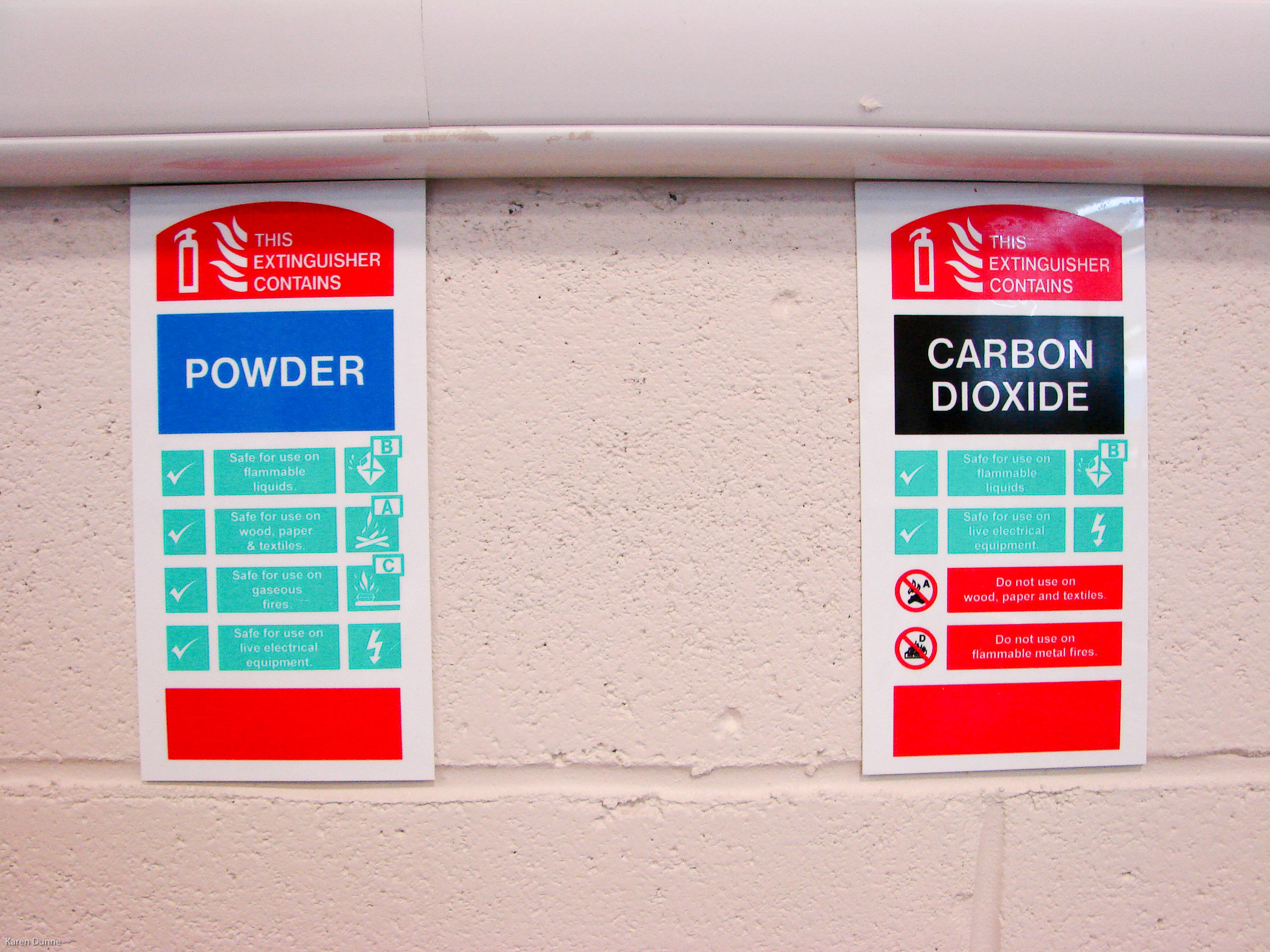

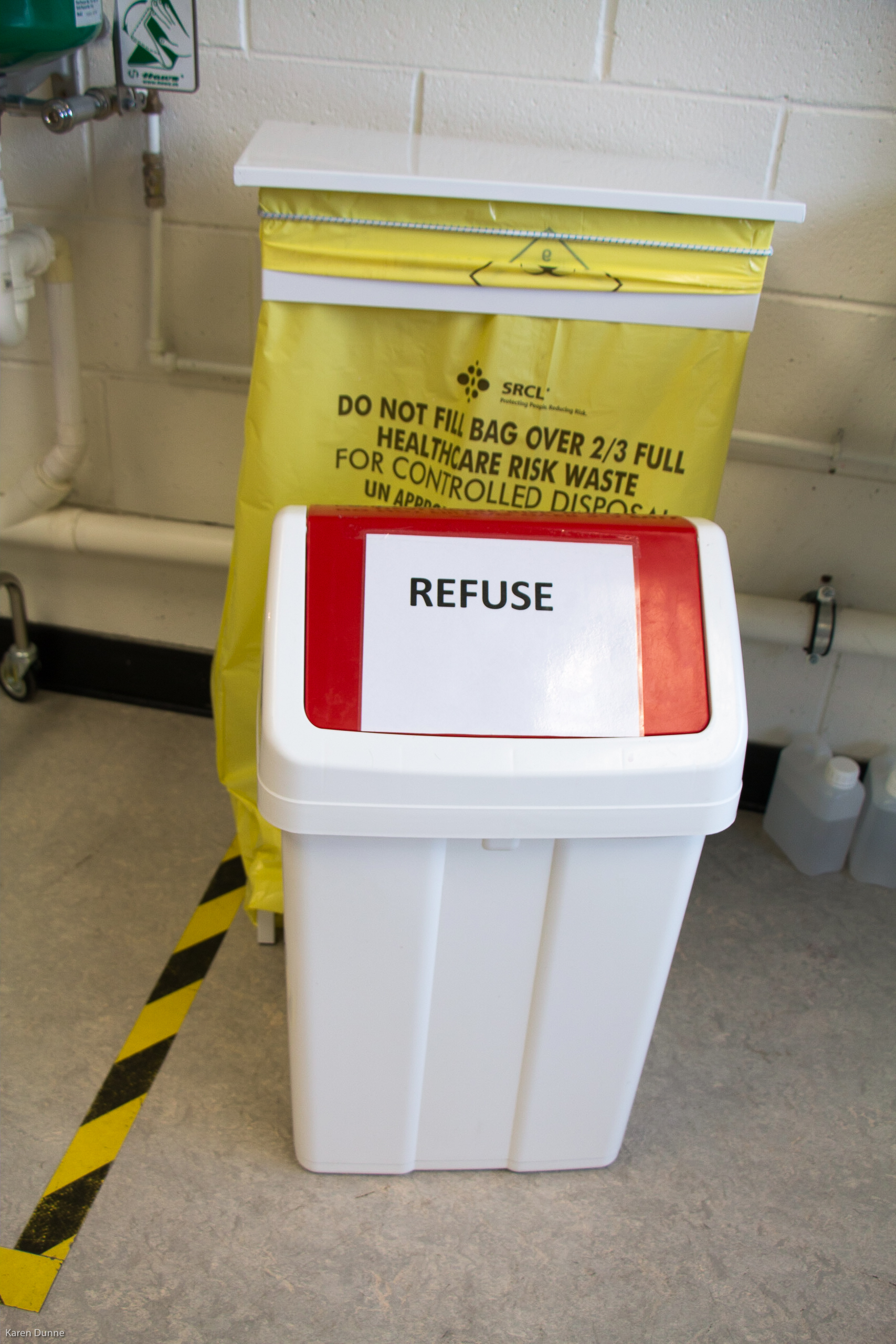

A range of refuse bins and clinical waste receptacles should be available to allow all waste to be correctly disposed of immediately. The lab should contain a first-aid kit, a fire extinguisher, a spills kit and an eye-rinse station.

The use of a lab manual or standard-operating procedure (SOP) lists will help ensure all staff follow the same procedures and adhere to correct testing protocols. External quality assurance controls will also enhance the reliability of your results.

Protective clothing

A Hoey-type (one with a closed lapel) long-sleeved and cuffed laboratory coat should be stored in the laboratory and put on immediately on entering. These coats should be kept fully fastened during use and laundered regularly (at least once a month and always if visibly soiled).

Protective goggles should be worn over the eyes when handling irritant liquids or chemicals - check the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for that substance, and read the label. If you wear glasses you should put the goggles over them, as the sides will protect you from splashes. Avoid wearing contact lenses when working in the lab.

Other protective clothing may be needed for certain tasks e.g. a face/dust mask if working with powdered chemicals/reagents. Again, check the MSDS/label for instructions before use.

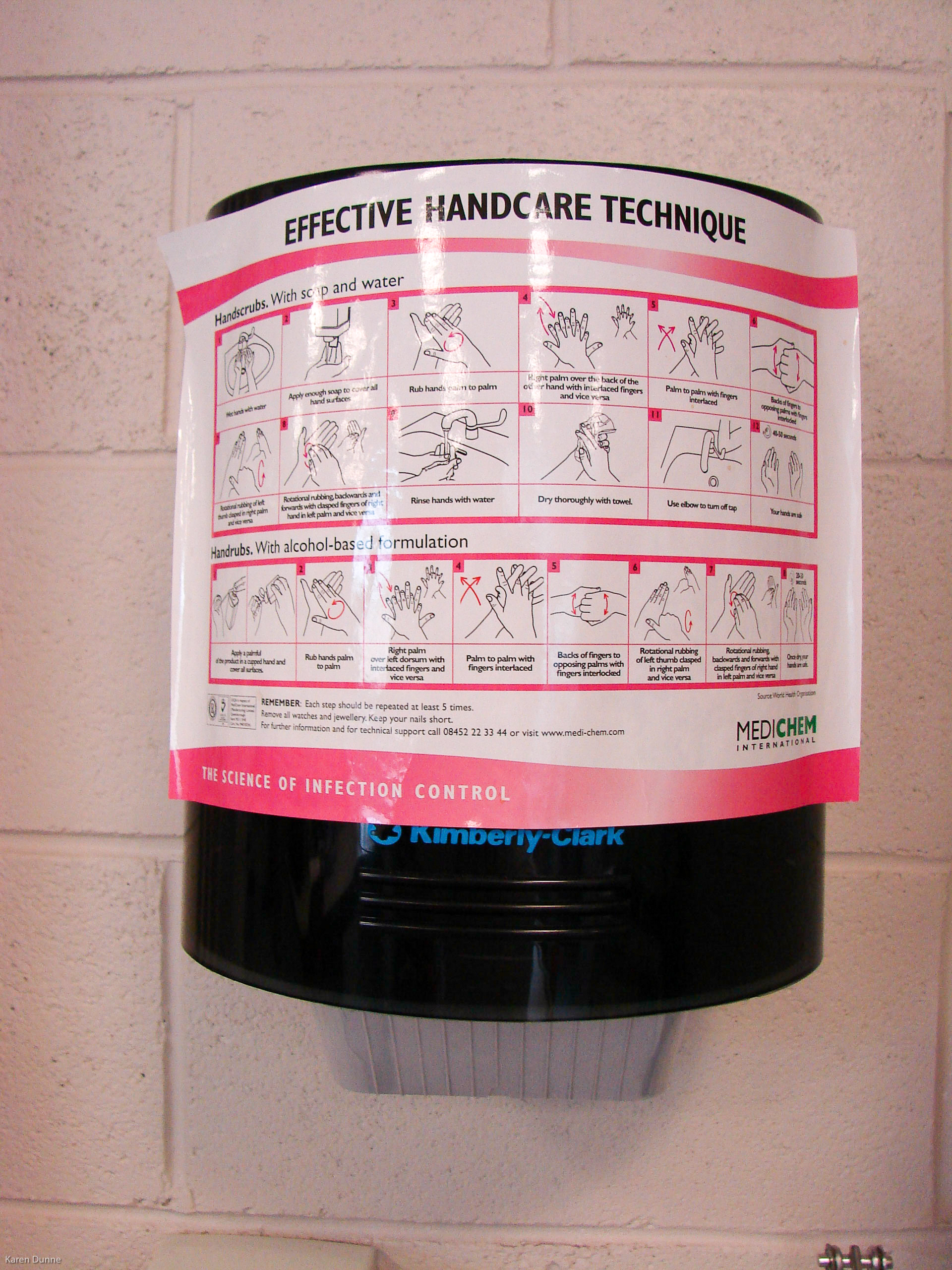

Hand washing

Wash hands on entering and leaving the lab, using a dedicated basin. You will need warm flowing water (from a tap that can be operated without touching it with your hands) and liquid soap. Hands and wrists must be free of rings, watches, long sleeves etc. A nail brush should also be available.

Use the six-stage hand washing technique (see video). Once finished, dry your hands thoroughly with disposable paper towel. If you must touch the tap to turn it off use the paper towel, to avoid re-contaminating your skin. The paper towels should be disposed of in a foot-operated or open topped refuse bin (N.B. they are not classified as clinical waste).

Air hand-dryers should be avoided as they spread microbes around the room. Reusable towels are also unsuitable as they harbour microbes unless laundered constantly, which is a waste of time and resources.

To add: picture of lab coats correctly fitted and stored, spills kit, label hazard warnings, classification of biohazards, face shield, pictures of wearing PPE for biohazards

Further reading:

Aspinall V. (2014). Clinical Procedures in Veterinary Nursing, 4th ed. Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier: London.

Bassert J.M. and Thomas J. (2016). McCurnin's Clinical Textbook for Veterinary Technicians, 8th ed. Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis.

Sirois M. (2014). Laboratory Procedures for Veterinary Technicians, 6th ed. Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis.